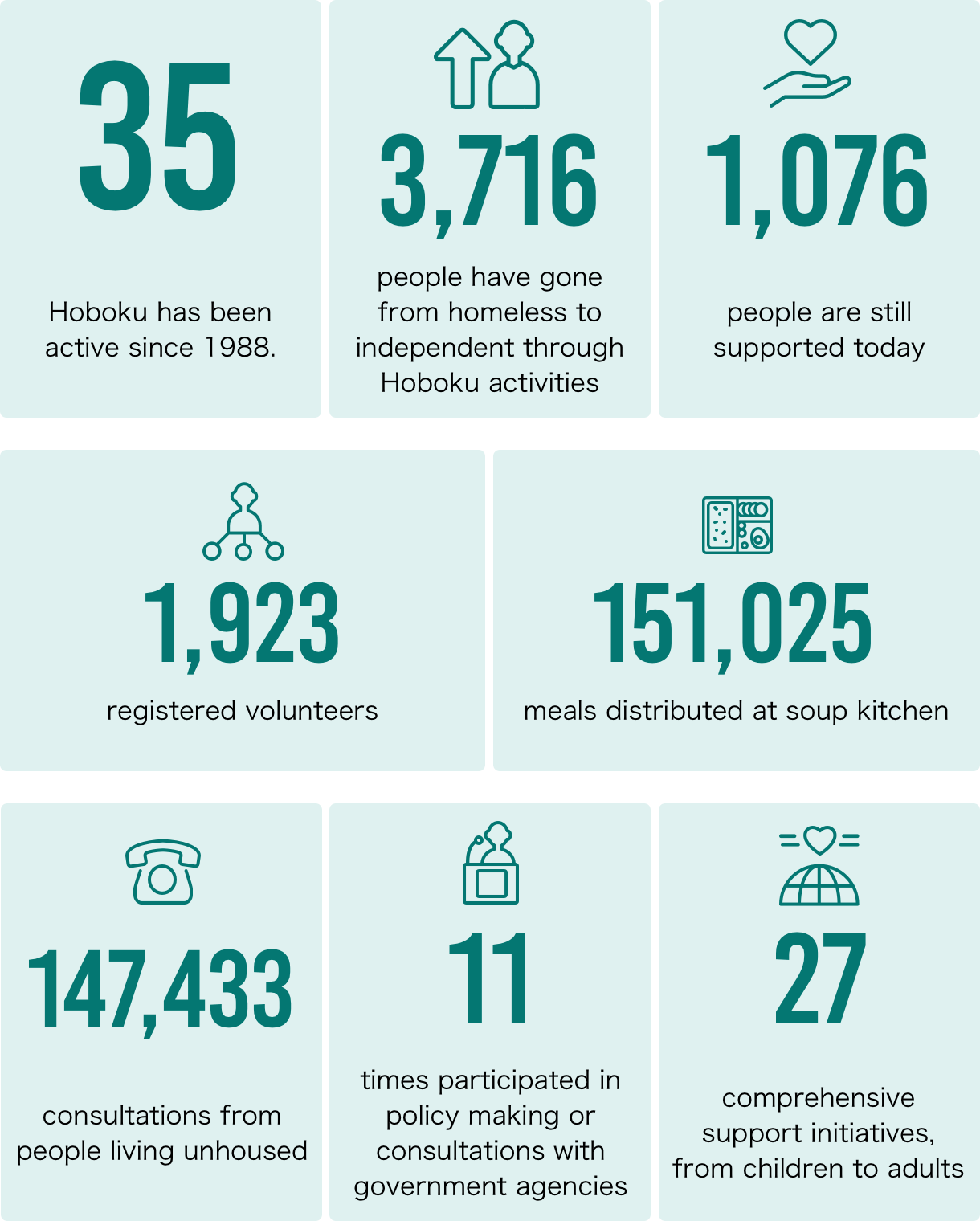

Hoboku in Numbers

The society we face

“I have no place within society.” “I’m in trouble, but there is no one I can go to, to ask for help.” “I am so exhausted from living, that I can’t even realize that I am in trouble.” – There are many realities of isolation and poverty around us, in both places that are visible and those that are not.

We want to create a society in which no one is left behind. A society where everyone can be accepted, just as they are. Amid today’s climate of ‘self-responsibility’ and emphasis on the role of the family, we will create a society where people can ask for help, without having to worry about anything.

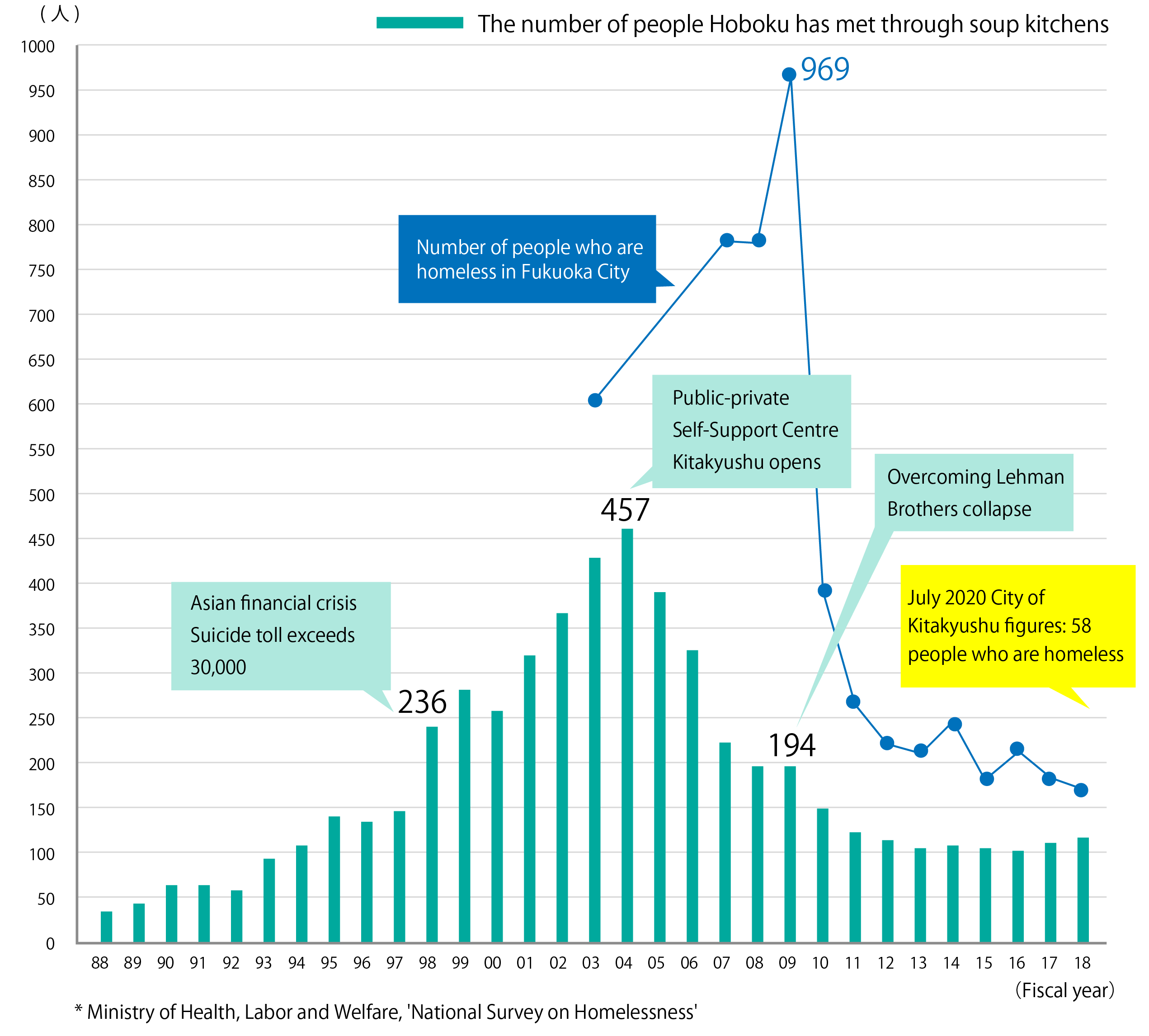

Through over 30 years of activity, the number of people in Kitakyushu who are homeless has decreased.

The number of people Hoboku has met through soup kitchens

The soup kitchen was started in 1988, and initially we gave meal boxes only to those people who were in a situation of homelessness. In the wake of the economic downturn in 2004, at times meal boxes were given to 457 people in a single session.

However, through subsequent activities to support people in becoming independent, even after the Lehman Brothers collapse the number of people who were homeless did not increase in the city of Kitakyushu, and this number continues to decline today.

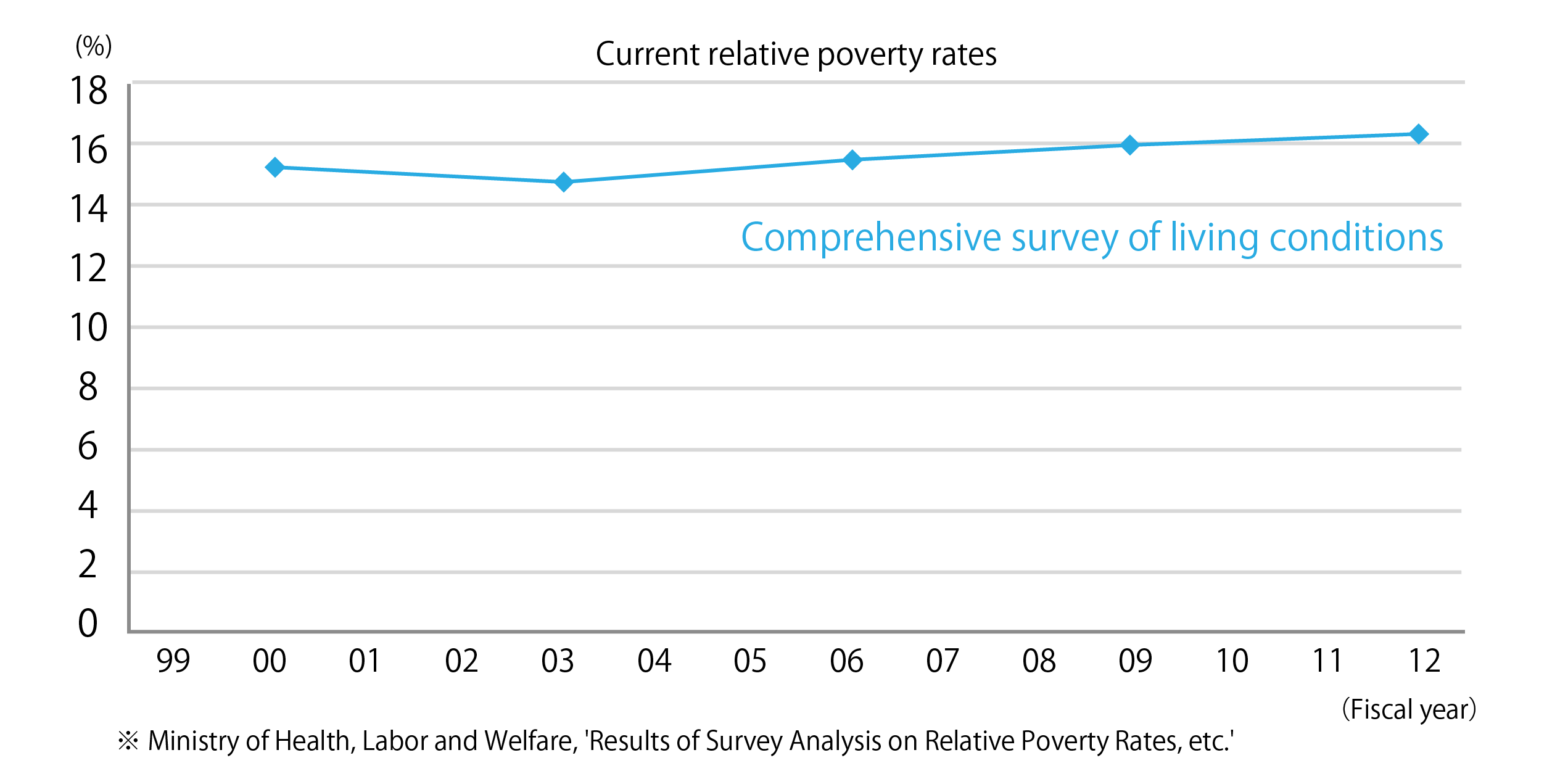

Although fewer people are unhoused, invisible poverty is increasing

Current relative poverty rates

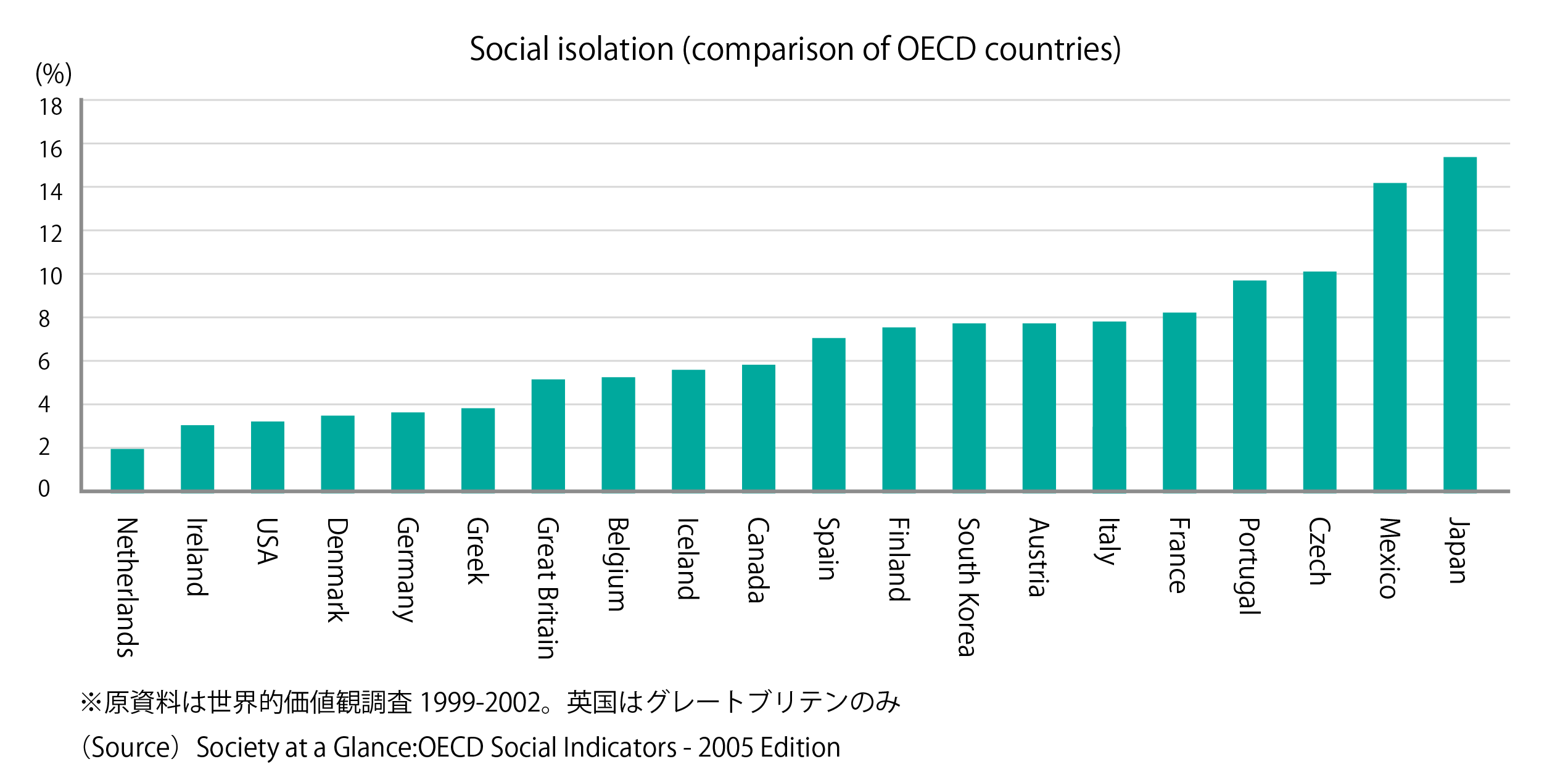

Social isolation (comparison of OECD countries)

The proportion of people living in relative poverty with an annual income of less than 1.22 million JPY has risen over the last 20 years.

In fact, one in six people in Japan are living in poverty. Even more serious is the high rate of isolation in the country.

Japan’s rank in the ‘social capital’ index, which measures the richness of human relationships, is 101 within 149 countries (2017). According to an OECD survey, the proportion of people who said they do not socialize with friends, colleagues or other groups of people rose to 15.3%.

As symbolized in the term “net cafe refugees,” poverty has become more difficult to see. Further is the issue of social isolation, where people do not have anyone they can turn to when they are truly in trouble.

The prevailing belief in ‘self-responsibility’ and the tendency of society to place too much burden on the family, creating a world that is difficult to live in, are by no means unrelated to these figures.

“I think it was when my wife left”

Mr Nishihara, who used to be homeless and now lives independently, gives public talks to children about his experiences. When asked “why did you become homeless?” he was quiet in thought for a while, before answering, “I think my homelessness began when my wife left.”

After his wife left the family home, Mr Nishihara continued to care for his son and his own parents. Once his son left home and his parents passed away, he was left alone, and became unsure of for what or whose purpose he was working, and then began to live on the streets.

Being able to work, when there is someone you are working for. Keeping your life in order, because there are people who will come and visit you at home. It is a very difficult thing for humans to live alone.

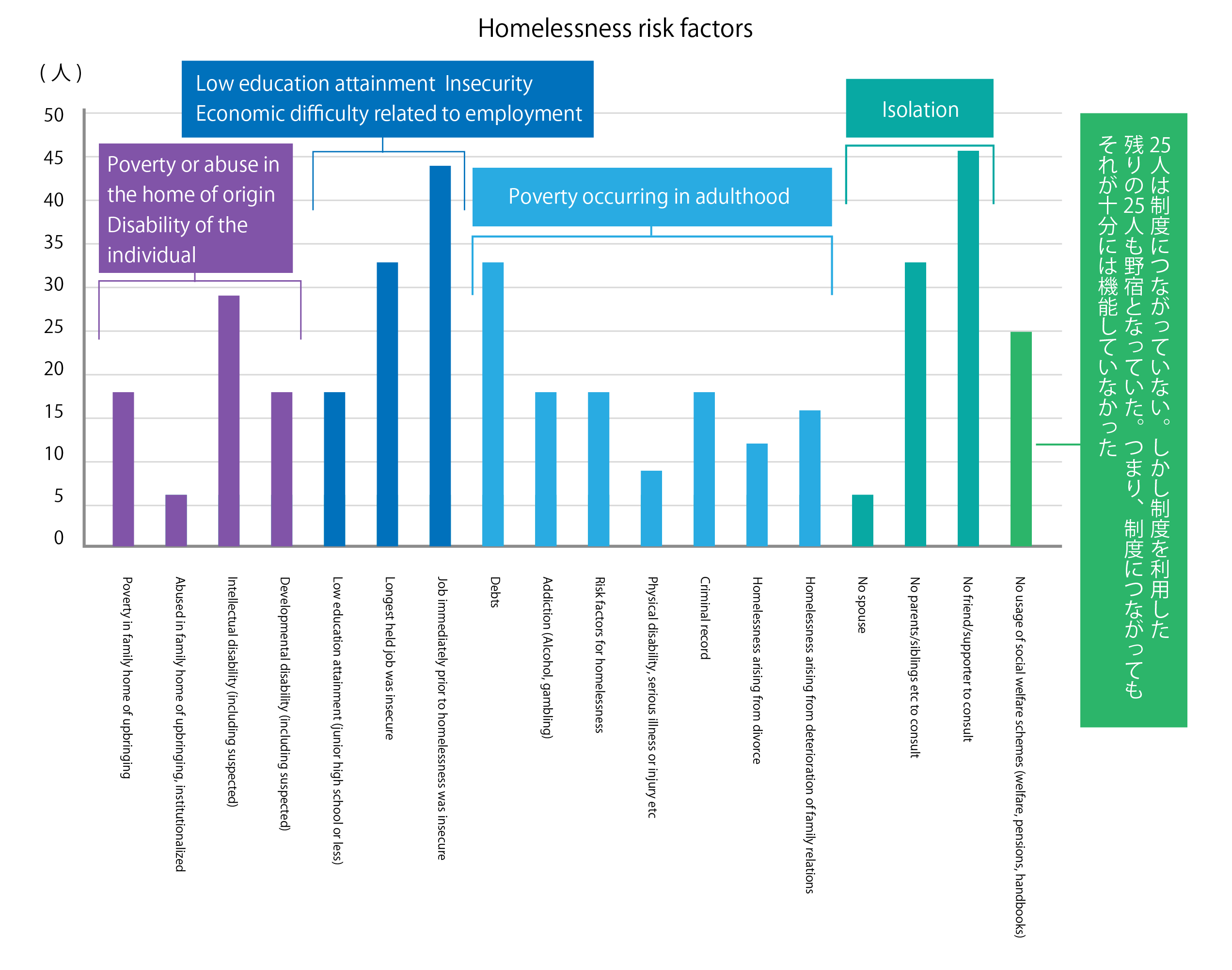

Homelessness risk factors

Being “Homeless” and “Houseless” is not the same

There are times when one may feel that they cannot see a role or purpose for oneself – “for what,” or no other person to do something for – “for whom.” In many cases, no matter how much financial support is provided, it becomes difficult to once again rebuild one’s life when connections with other people and with society have been severed.

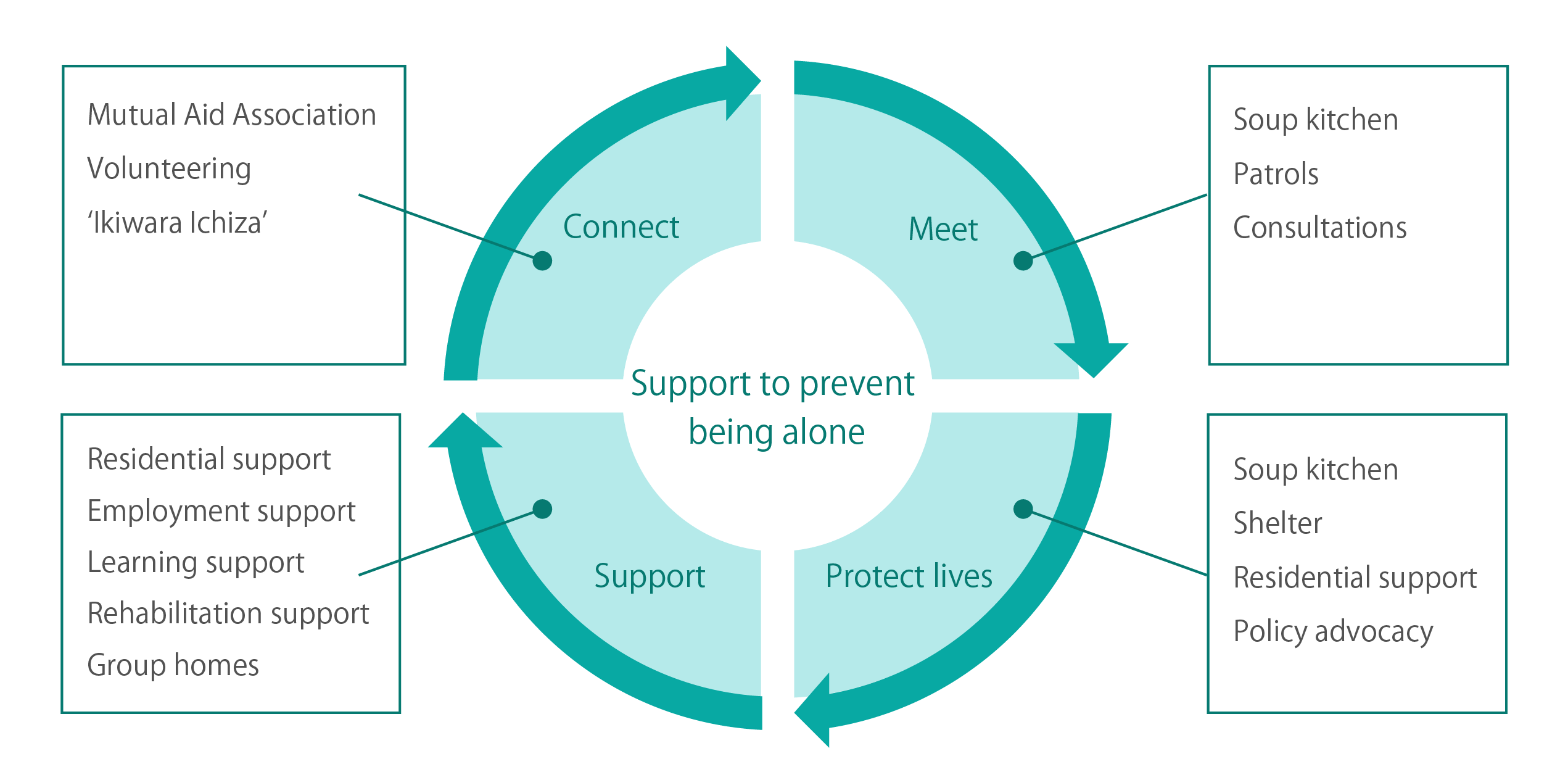

This is why Hoboku considers the issues of being “homeless” (societal isolation) and “houseless” (economic hardship) as distinct from each other. For people in a situation of houselessness, we consider: “what does this person need?” Whereas for people in a situation of homelessness, instead, we think of “who does this person need?”

Our work does not end when a person is provided a guarantor and able to enter an apartment. We continue to build their relationship with society, and to be someone to whom they can at any time ask for help. We create a support structure that addresses both economic poverty and societal isolation at the same time.

More than 30 years have passed since we began our activities, and the scenes of poverty seen on the street have now spread throughout society. Poverty, inequality and isolation are now becoming the norm. If you cannot think of who you would turn to in a time of need, then you may yourself be someone “housed, but homeless.” We want to change such a society. From Kitakyushu to all of Japan, we will expand a society in which no one is isolated.

Our Principles and Values

Point1 There is meaning in living

We live in an age in which words such as “a life without meaning” are spoken openly. Hoboku stands up against this, asserting that there is meaning in living. A society of co-existence is important. However, even if we are not able to co-exist, even if you are living in isolation, there is meaning in the very fact of being alive. When society questions things such as the meaning of life, the meaning of existence, or productivity, even if we cannot find the answer, Hoboku declares that “there is meaning in being alive right now.” This is the universal value we hold most important.

Point2 Not forcing everything onto the family

As seen in the phrase ‘the 8050 problem’ (where 80 year old parents and 50 year old Hikikomori (people living isolated from society) cohabit), the ‘family’ is reaching its limits. The reality is that it is not possible to respond just with self-responsibility and the responsibility of family members. Can society take on the role of the ‘family?’ This was a key theme for Hoboku. The most symbolic situation, for example, is that of funerals. Landlords were refusing to rent to tenants, because of lacking family members to take on future funeral or post-mortem arrangements in the case of their death. Through Hoboku’s Mutual Aid Association taking on this role, such refusals have now ended. Hoboku aims to socialize family functions from first meetings to end of life care in such a way.

Point3 Not turning anyone away

The strength of NPOs is freedom. In principle, they can do anything. Hoboku takes advantage of this asset to creatively develop projects based on encounters with individuals, and according to need, create structures of collaboration. This is our greatest characteristic. On the other hand, because we do not utilise existing systems, we face challenges in expertise. In order to enhance our expertise, we are now preparing to establish a social welfare corporation. As such corporations are based on existing systems, the possible beneficiaries are limited. But, through coordination with the “broad and free” NPO Hoboku, we will together realize the way of being in which we do not turn anyway.

Point4 What is “being productive”?

At Hoboku, we see “being productive” as “self-realization.” Unlike today’s society, which limits productivity to the creation of money or things, we believe that being productive is when a person is able to live as themselves, in their own way. A highly productive society is one in which each person is able to fully realize their own capacity and individuality. Hoboku’s initiatives exist in order to realize the irreplaceable self that each person is given. However, both finding and realizing the self are not things that can be done alone. Hoboku struggles against social isolation, and meets and accompanies people in order to achieve this self-realization.

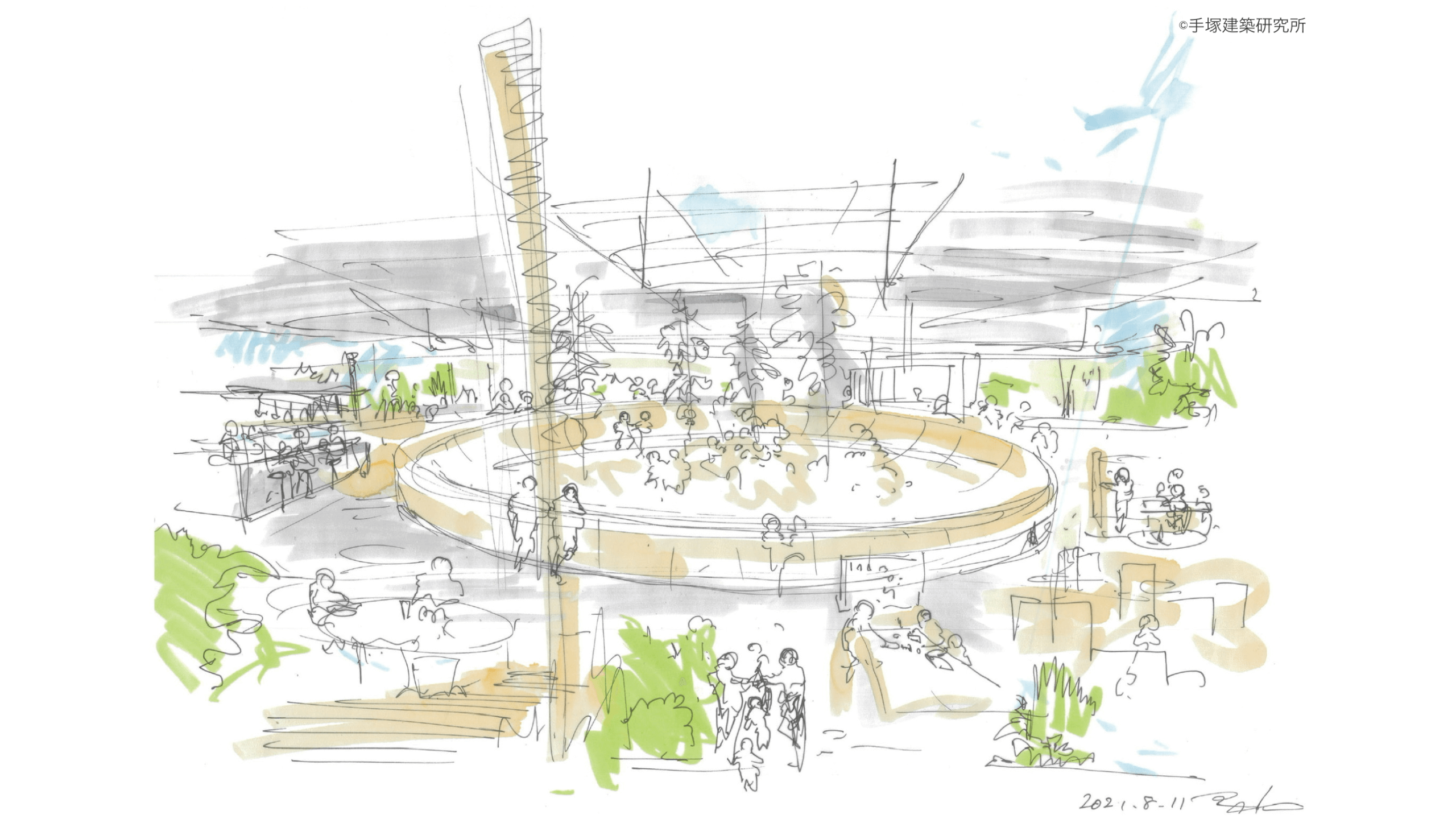

The “Town of Hope Project”

The “Town of Hope Project” is an initiative led by Hoboku to transform the site of a former gang headquarters into a community hub for a society of co-existence. For many, Kitakyushu has an image of gangs. The name of the project reflects the desire to shift from a “town of fear” to a “town of hope.”

Today, various changes in society such as the increase in single-person households and the weakening of local community relationships are making problems of loneliness and isolation more serious throughout Japan.

In order to alleviate social anxiety caused by such problems, there is a need for a place where people can go for advice when they feel worried, and where everyone can meet and spend time together on an equal basis.

The “Town of Hope” hub facility will be open to all generations, from children to the elderly, and provide both a place to be and a role to play for all.

The four-storey building will include a large hall which can be freely used by the local community on its first and second (partial) floors. In addition, it will host spaces including a one-stop consultation service, a Kodomo Shokudo (Children’s Cafeteria) to support children and their families, a learning support centre, and facilities for everyday support of the local community.

On the third and fourth floors, a “relief centre” for use in daily life by people who are experiencing difficulties in living. This will also be made open to the local community as an evacuation centre in the case of a disaster.

We are now seeking donations for the construction of this facility, and greatly appreciate any possible support.

* Image of the completed facility (2025)

Goals of the Town of Hope

1. From a Town of Fear to a Town of Hope

We will re-create the site of a former gang headquarters into a place where many people can spend time with a smile.

2. A place where people can ask for help

In this age of so-called ‘self-responsibility,’ we aim to create a place where people can mutually help others and be helped themselves.

3. A big family

We will create ‘family-like’ bonds throughout, going beyond what had previously been considered as ‘relatives.’

4. Raising children together

By the whole community together supporting children and their families, we aim to break the cycle of poverty and share experiences and mutual goodwill within society.

5. From Kitakyushu to all of Japan

We will realize the model of a community-based, co-existing society as a pioneer, and spread the Town of Hope throughout the country.

Message from Okuda Tomoshi, Hoboku President

In December 1988, we began to walk around the town at night, visiting people who were living on the streets. We were just a few volunteers, speaking with people, onigiri rice balls in hand. Our activities began in this way, wondering what we could and should do. We walked around the town, sitting by people’s sides and listening intently. We took notes, trying to make sure not to miss a single word. Within those words would be what we should do. Sometimes we were told off, told not to come, but we waited and remained, believing that ‘the time’ was sure to come.

In the year 2000, we registered as a Non-Profit Organization. On that day, we declared that we would work towards being able to disband as soon as possible – aiming to create a society where our activities would no longer be needed. Our missions were to ensure to not let anyone die on the street, to get as many people off the streets as soon as possible, and to create a society where people do not become homeless in the first place.

In this age of increasing isolation, our basic stance has been to never leave anyone alone, never turn anyone away, and to stay connected. Without being restricted by existing systems, we built up the necessary systems from the meeting with each individual. The fact that such activities are not based on limitations due to existing systems led to our way of being that does not look at people according to their social categorization. In the first place, there is no person named “homeless.” Each and every person has a name, Yamada-san or Tanaka-san. It is from this encounter with the individual that everything begins, and we continue to believe in the responsibility that comes after having had such an encounter. Our activities do not stop at supporting people to become independent. They have taken on the style of covering from “the first encounter to end-of-life care,” and accompanying people throughout their lives.

In 2014, 25 years after having begun our activities, we took on the name “Hoboku.” In Japanese, this name means to embrace the raw and rough wood that is cut from the mountains. To us, this represents a culture of opposition to trends in mainstream Japanese society, where “reasons to refuse” and turn people away such as “self-responsibility” run rampant. Poverty and inequality have already become the norm in Japan. Realizing that it is not possible for us to disband, we have now decided indeed not to, and to continue our work.

We strive for a society that embraces; a society that has given up on reasons to refuse. Our activities began with supporting people living on the streets, and have expanded to supporting poverty-stricken and hurting families, children who are not even able to cry, people in further isolation, those who have lost their jobs, who feel difficulties in living, who have committed crimes, who are living with disabilities, the elderly, and those who have challenges in securing housing. The number of initiatives we now implement has reached 27. This is all for the purpose of fulfilling our responsibility, having encountered these people and issues.

We aim to provide support in the form of accompaniment. In addition to more traditional problem-solving support, we place value on staying connected, even if we cannot resolve the problem. When such accompaniment becomes a premise of society, we will all be able to ask for help. As Hoboku, we aim for a society in which anyone can say that they need help.

We hope that you will support these efforts.

![「ひとりにしない」という支援 NPO法人 ほうぼく[抱樸]](https://www.houboku.net/wp-content/themes/houboku/assets/images/Logo.svg)

![「ひとりにしない」という支援 NPO法人 ほうぼく[抱樸]](https://www.houboku.net/wp-content/themes/houboku/assets/images/Logo_mini.svg)